A divisional director from the Manpower ministry gave testimony last week at the Committee of Inquiry looking into the Little India riot. Based on a report in the Straits Times, his statements more than support a view that I have long held: there is a strong tendency in this government to confuse theory with practice. There is unwarranted faith in policy papers penned in cloisters. Either there is naive ignorance of the shameful reality out there, or a resistance to unearth empirical facts, or both. That dark reality — often dimmed further by half-hearted or non-existent enforcement — stands in stark contrast to the sunny scenario as painted by stated policy. Yet more (tax-payer-funded) effort is expended by civil servants in protecting an almost self-deluding faith in the theory of how things ought to be (while throwing stones at critics) than in uncovering how things actually are. Remedying the failures in policy seems quite far down the list of priorities.

There are four arguments made by Kevin Teoh, divisional director of the Ministry of Manpower’s (MOM’s) foreign manpower management division, which are egregiously off the mark. They show beliefs that are detached from reality.

1. There are no abandoned foreign workers;

2. Out-of-work foreign workers can seek alternative employment (subject to permission);

3. MOM has ensured that foreign workers all know their rights;

4. Untrue that workers are forcibly repatriated.

I will deal with each further down. Forgive me for a long post (5,300 words), for I intend to rebut his point not merely by asserting to the contrary, but through detailed description of how things actually are in the real world and how those observations indict departmental beliefs and policies as expressed by him.

Re: quality of information

Teoh was testifying before the Committee of Inquiry set up to investigate the background, among other things, to the riot on 8 December 2013 in Little India. His appearance followed a week after the president of Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2), Russell Heng, testified before the same committee.

Disclosure: I also serve as vice-president of TWC2, though this post here on Yawning Bread is written in my personal capacity. But this double role that I have also means that I speak here with authority. I probably engage with, and help brainstorm solutions for, more foreign workers in a month than Teoh himself might have spoken with in his entire lifetime. In addition, I oversee social workers and volunteers who similarly deal with many more workers in person, and they report to me all the kinds of problems they have to deal with.

|

Teoh might retort that he too oversees a huge department that “facilitates the well-being of foreign workers” (seriously, that’s the eerily Orwellian way the department describes itself) but he should be aware that information flows within bureaucratic organisations are prone to filtering. There is always a bias against unflattering information — lost as cold numbers froth up to desk-bound directors.

Moreover, as discussed in the last section of this article, government departments may never get good data from vulnerable communities due to an inherent tension and reflexive distance between power (as represented by ministry departments) and the vulnerable. See yellow box above left for a somewhat comic example.

|

Not only is the process of data collection and analysis inherently problematic within bureaucratic organisations when they try to deal with vulnerable communities, most government departments in Singapore — and MOM is one of the major culprits — are suspiciously opaque about how their numbers and statistics are obtained. Whenever it is convenient to them, a number is fetched from a department’s bowels, terminology not explained, methodology, definitions, and comparative data over longitudinal periods (10, 20 years) not provided. Most times it is impossible to discern meaning from such isolated information. Over time, as this habit is observed again and again, ever contemptuous of the public’s intelligence, the overall credibility of the government department just sinks.

And when divisional directors make bald assertions on the basis for such disconnected, suspect data, they shouldn’t be surprised when they are mocked on social media.

It bears repeating that information is collected only when pertinent questions are asked. But, as I mentioned in the opening paragraph, there is so much faith invested in theory, and so much unwillingness to uncover facts that undermine the comfort of theory, that, based on my own observations of MOM, pertinent — nay, pressing — questions are seldom asked.

Next, we move on to deal at length with the assertions that Teoh made. They were in response to the points made by Russell Heng to the Committee earlier.

1. Abandonment

Divisional director Kevin Teoh of MOM’s foreign manpower management division told the committee he was surprised that rights group Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2) had testified it was feeding some 350 “abandoned workers” at its soup kitchen daily, given that the Employment Act clearly placed the responsibilities of housing and feeding work permit holders on their employers.

Last Tuesday, TWC2 president Russell Heng had told the committee workers “basically have to resort to charity to survive in Singapore” as they waited for their complaints – usually salary arrears or work injury compensation – to be sorted out.

While the law required employers to care for their workers in the interim, Dr Heng said TWC2’s experience was that “in practice, this is not the case”.

Mr Teoh disagreed with the notion that MOM abandoned these workers and said when an employer is unable or unwilling to fulfil its obligation, the ministry would step in to house the worker and provide food — sometimes in partnership with help groups such as the Migrant Workers’ Centre — while a complaint is investigated.

“Sir, like you, I was equally surprised when he made the assertion here,” said Mr Teoh. “We are now checking with him specifically which are those workers he is referring to. If he has the necessary information, we’re prepared to look into it.”

— Straits Times, 19 March 2014, MOM: Workers told of rights even before coming here, by Lim Yan Ling

Teoh should ask his boss, the Minister for Manpower Tan Chuan-jin, what he saw when he (Tan) visited TWC2’s soup kitchen in 2011. I am sure Teoh would be welcome to visit himself and speak to the workers there, rather than merely sit at his desk, asking and looking at “necessary information”.

What exactly is the profile of a typical abandoned worker? He would be someone who had suffered a workplace injury. The employer would be responsible under the law to provide medical treatment, medical leave wages, housing and food. If the injury is serious, this could stretch for months, even years. Keen to avoid costs, many employers exert great pressure on the worker to give up all claims (including his right to medical treatment) and be sent home. If necessary, threats to send in strong-armed, tattooed, gangster-mouthed repatriation agents are loudly made. There are enough anecdotes circulating in migrant worker communities of fellow workers being forcibly repatriated to make such threats very real.

Fearing that repatriation agents would come in the middle of the night to seize him, the injured worker would flee his company dormitory. He would typically borrow money from friends to pay the $250 per month for a flea-infested bunkbed in an unlicensed flophouse (example above). Those with no willing friends would have to sleep rough.

|

The worker would be able to continue seeing his doctor — but see box at left about limitations. However, the employer now thinks it is freed from its obligation to provide housing and food. As for medical leave wages (as specified under the law), employers avoid paying until a worker approaches TWC2 for help. We then press MOM for action; most times (fortunately), the ministry is able to prevail on the employer to pay up.

As Russell told the Committee of Inquiry, the worker depends on charity: on the goodwill of his friends to lend him money, and on TWC2 for the meals we provide at our soup kitchen.

Teoh “disagreed with the notion that MOM abandoned these workers”. This can be parsed at various levels. At one level, this is not untrue: Russell didn’t point and say that it was MOM who abandoned the workers. One could say that the abandonment is primarily traceable to the employer. In TWC2’s experience, when a worker’s complaint is brought to MOM, officials do some degree of fire-fighting. How effective MOM is depends on the problem. With medical leave wages, MOM is generally effective in getting employers to pay up. On the other hand, with housing and food, MOM has no effective solution, and hasn’t even got around to realise that they don’t have an effective solution.

But that’s precisely the problem. Although, as the newspaper reported Teoh to have said, “the Employment Act [sic — it should be the Employment of Foreign Manpower Act] clearly placed the responsibilities of housing and feeding work permit holders on their employers,” in practice this is often not the case. To fail to design a better system when the present one does not deliver is a form of abandonment too.

As an analogy, let’s put it this way: If a factory produces ten percent defective products, but the manager tries very hard to repair them when alerted to it, yet never gets around to the root of the problem to reduce the defect rate, would you still have cause to say he is neglecting his job?

|

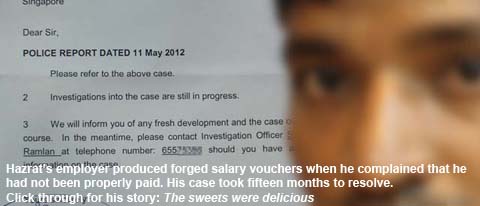

In 2012, Shahin’s case was featured in the Straits Times. His was a salary case. He had not been paid and when he complained, the employer produced forged salary vouchers to ‘prove’ otherwise. MOM could not rule that these were forged, since Shahin couldn’t provide copies of salary vouchers on his part. The reasons why should be obvious: Firstly, since he wasn’t paid, he wouldn’t have any copies, would he? Secondly, even if he had been paid, MOM gives so much discretion to employers to not give copies of payslips to employees that Shahin’s lack of documents neither proves this nor that. So the case dragged on with no resolution. Shahin was homeless and sleeping rough. When the newspaper featured his plight, MOM offered him a bed in a dorm in (if I remember correctly) Lim Chu Kang. Shahin turned it down. His secondary reason was that MOM also required him to report to the ministry every week to get a stamp extending his pass to stay in Singapore. Where would he find the money to pay for the long bus rides to MOM? Saying “Here’s a bed in Lim Chu Kang” is no solution at all when he has to fork out money to go back and forth. But his primary reason for turning down the bed was that giving him a bed doesn’t solve the root problem, which was the lack of progress in his salary claim. MOM may brag that they have fire-fighting mechanisms in place to “solve” housing problems, but as you can see, it’s hard to recognise this as a solution when workers would rather sleep rough nevertheless. |

Even with medical leave wages, fire-fighting when alerted is often only good for a worker when he is entitled to medical leave wages in the first place. Many are not. The law does not mandate medical wages be paid for all the months till the worker is fully healed and goes home. It only mandates medical wages if

(a) a doctor continues certifying him as unfit to work (i.e. providing a medical certificate “MC”);

(b) if MOM determines that the injury is work-related.

Many workers fail to meet one or the other of these conditions and fall through the crack.

Re (a), at some point in the recovery process, a worker no longer gets MCs. But by then, instead of going back to work (which is the assumption inherent in our legislation), he has no job to go back to. The company terminated him soon after learning that his injury is a serious one, possibly in order to free up the work permit, so as to hire a new worker desperately needed to keep the workforce up to strength.

|

Yet, the injured worker cannot go home either, because the compensation process led by MOM drags on — sometimes for over a year.

Re (b), which is a far more serious matter, employers often deny that an injury took place at work, so as to lessen their cost liabilities. In support of their denial, evidence is obliterated or tampered with, as TWC2 has all too often been told. MOM tends to take altered evidence at face value and rule that the injury is not work-related, thus denying workers their right to treatment and compensation under the law.

It is easy for employers to tamper evidence (and hard for MOM to see that it has been tampered with) because the work permit system designed by MOM gives enormous power and discretion to employers. Yet MOM is not about to change the system.

Between (a) and (b) and sometimes both, a worker is stuck in Singapore. He is too injured or not allowed to find alternative work. He is jobless and penniless… and has to depend on charity.

It’s hard to see how one can say such a situation does not constitute abandonment. But if you still think the term is inappropriate, then call it “imprisonment by the system”.

2. Workers can find alternative work

He also clarified that while a complaint is being investigated, there is no ban on a worker seeking alternate employment as long as permission has been granted him by MOM.

— ibid.

This statement by Teoh glosses over the problem. The first hint that it means less than what it appears to mean lies in the words “as long as permission has been granted”.

Injured workers — the great majority of those who seek help at TWC2 — are routinely denied permission.

Workers with salary claims, on the other hand, often do get permission to seek alternative employment, but TWC2’s experience is that many (perhaps a majority, though we haven’t been counting) come back to us to say that no jobs are available without having to pay $1,000 to $2,000 to the prospective employer.

(Our guess is that many of those who managed to get new jobs, did so by paying or by agreeing to have the sum deducted from their future salaries.)

The reason bosses demand payment with impunity is that the system designed by MOM is defective.

The reason bosses demand payment with impunity is that the system designed by MOM is defective.

Unlike Singaporeans looking for jobs in Singapore — i.e. jobs for which the employers aren’t allocated work permits — foreign workers looking for work permit jobs find themselves competing against hundreds of millions of Indian, Chinese, Burmese, Bangladeshis, etc. Naturally, the market sets a price. Whilst it is obvious that making people pay for jobs is unethical — and in fact it is illegal for employers to take kickbacks — this is an example of market failure that MOM (despite being armed with the law) makes little effort to remedy.

The practice not just persists. It is widespread. Effectively, employers enjoy free labour (through the kickback) for the first few months a worker is on the job. Such an employer is then able to tender more competitively for construction or cleaning contracts. Hence, dishonest employers drive out honest ones. Such a trend is a cancerous growth in our economy that MOM doesn’t even see as a problem deserving urgent and rigorous action.

For Teoh to merely say that there is “no ban” on workers seeking alternative employment, without his ministry attending to the reality that there are no jobs to be had without workers having to pay more, is to reveal that very tendency I mentioned in my very first paragraph: putting more effort at painting a rosy picture and defending the untenable, than in getting to grips with reality.

3. MOM ensures that workers know their rights

The ministry begins education efforts even before a worker arrives in Singapore, added Mr Teoh, with employers required to put in writing the wages, deductions and other terms in an employment letter to the worker in his native language.

— ibid.

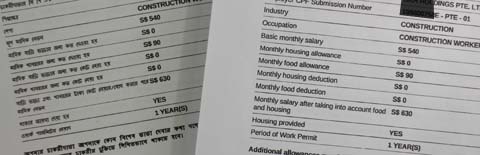

Teoh was referring to the In-principle Approval for Work Permit (IPA), a set of letters automatically generated by the ministry. An IPA contains details of employment terms submitted to the ministry by the employer at the time of applying for the work permit. The set consists of three letters.

1. In English, addressed to the employer confirming that an in-principle approval has been granted

2. In English, addressed to the worker, telling him the same

3. In the worker’s native language, addressed to the worker, telling him the same.

Above are extracts from a Bengali- and English-language IPA for the same worker, i.e. #3 and #2 letters, so readers can see what they look like.

|

The employer is required to send #2 and #3 to the worker before he flies into Singapore, as the worker is required to present at least one of these letters at Immigration. But very often, the company or its agent gives only #2 (the English version) to the worker, when the latter may not be able to read English. #3 disappears without a trace.

Again and again, I meet workers who are surprised to hear from me that a native-language version existed once upon a time, and should have been given to them. “No kidding? You mean there was a Tamil version, and I should have received it?” is the typical response.

Fortunately, most workers can figure out, perhaps with the aid of a friend, what the English version says, but some workers (especially from China) have no friends who can read any English at all.

I have long argued that the simplest remedy is to have both the English and native-language sentences run together on the same page, rather than print them on separate sheets of paper. This way, there’s no way the native-language version can disappear and not be given to workers prior to departure. But the mind-boggling thing is that such a simple solution has not occurred to MOM. Or is it that MOM, ever reliant on the maxim ‘theory must surely be practice’, doesn’t even know that there’s a problem? That employers and agents have all along been throwing away #3 and defeating their best intentions?

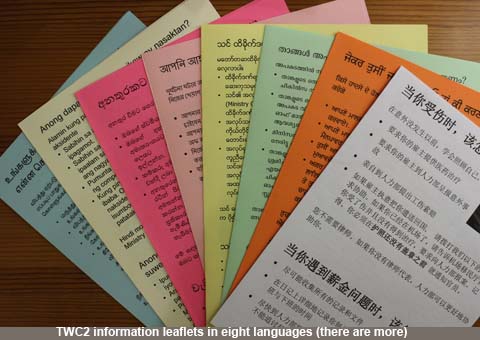

Guidelines on worker obligations and rights are also issued to overseas training centres.

The guidelines are given once more to all workers when they are fingerprinted in Singapore for their work permit cards, and they have to take mandatory exams to test their knowledge of employment rights before they begin work. “So, collectively, we don’t believe that the worker does not know his basic rights, does not know where to go,” said Mr Teoh. “There are many avenues available to him.”

— ibid.

This is very strange indeed. Despite having seen hundreds, perhaps thousands, of workers in the past few years, I have yet to have one of them mention or show me any “guidelines” given to them at the time they were fingerprinted at Tanjong Pagar (the office where work permits are issued). Nor has any worker mentioned any “mandatory exams to test their knowledge of employment rights before they begin work”.

I shall propose to my colleagues at TWC2 a simple survey to check this assertion by Teoh.

Quite the contrary, most workers who come for help are at a loss what they can do, or what they are entitled to.

There have been a few occasions when a worker mentioned something about a briefing conducted at his training centre in India or Bangladesh before he came to Singapore, but these recollections were usually along the lines of ‘it was all a big mumble and rushed through’, or that the briefing mostly consisted of stern warnings that

There have been a few occasions when a worker mentioned something about a briefing conducted at his training centre in India or Bangladesh before he came to Singapore, but these recollections were usually along the lines of ‘it was all a big mumble and rushed through’, or that the briefing mostly consisted of stern warnings that

- Singapore has very strict laws

- workers must obey the law

- must not take drugs

- must not litter

- not allowed to get married here

and so on.

4. No forcible repatriation

It is also untrue that workers are being forcibly repatriated, said Mr Teoh, another issue raised by rights activists, including Dr Heng and Workfair Singapore’s Mr Vincent Wijeysingha, as it is a topic covered in the materials provided to guest workers.

He told the committee that workers could inform immigration officers at the checkpoint if they had ongoing employment-related complaints that were being investigated by MOM. The ministry dealt with 23 such cases flagged by the Immigration and Checkpoints Authority last year, he added.

— ibid.

Firstly, there appears to be a contradiction between saying that it is untrue that workers are being forcibly repatriated and then citing a figure of 23 cases “flagged” at the airport last year.

Secondly, were the employers of these 23 prosecuted for trying to pack workers off? I have yet to hear of a case where an employer is charged.

Thirdly, does it not stand to reason that many more cases are likely to exist? Cases that slipped past Immigration authorities? The “safety net” only works like this: workers who feel they are being unfairly repatriated (i.e. without their injury or salary claims resolved) have to walk up to an Immigration officer and say so. If workers don’t know this is possible or don’t take the initiative to do so, nothing would be “flagged”.

What I know is that each month when I participate in TWC2’s Outreach Sunday — we go out to distribute flyers in native languages to workers in various parts of Singapore, and I meet between 50 and 250 workers each Sunday depending on which area we’re covering — I take the trouble to point out to most workers I meet the paragraph in our pamphlet that advises them to walk up to Immigration should they be be forcibly hauled to the airport.

Without exception, every worker whom I point out the paragraph to is surprised to learn that this is possible. None has ever said he knew of this before. Yet Teoh spoke as if this is common knowledge among workers, and ‘proof’ that his department has done loads to protect workers.

I won’t be surprised if most or all the 23 workers who appealed to airport Immigration for help last year had been informed priorly by non-government organisations (NGOs) of this right. But we can’t reach every one of them; NGOs don’t have the resources to cover every worker in Singapore. So, the greater likelihood is that many more workers didn’t know and have been sent home unfairly. This is further supported by reports from their co-workers who come to TWC2 weeks or months after the fact.

Here’s a typical story from my interviews notebook (workers mostly speak in pidgin English, here the sentences have been polished for my readers’ benefit):

“My employer had ten workers, all not paid for four months. Two months ago, two men complained to the boss about their salaries but they were sent back the next day. That’s why the eight of us didn’t dare complain for another two more months, but now we can’t stand it any more. We are scared, but no choice, we have to complain now.”

Another typical account, from an injured worker, went like this:

“Last year, another worker was also injured. At first, he was treated at a hospital. But when it was due for a follow-up appointment, the company lorry, instead of taking him to hospital, drove him straight to the airport. That’s why, now that I have an injury too, I need to get out of the company dormitory as fast as I can. I have to stay somewhere else that is safer. Can TWC2 help me find a place to stay?”

For the ministry to assert that forcible repatriation doesn’t happen is just not credible when we keep hearing such accounts.

To be fair, the number of attempts at forcible repatriation has gradually fallen over the years. My general impression is that reports have become fewer. Why this is so, I don’t know. One possible explanation I have is that employers are managing to achieve the same objectives — denying owed salaries, avoiding responsibility for medical treatment, medical leave wages, housing, etc — by doctoring evidence, forging salary vouchers and denying that accidents happened at work, without now having to repatriate workers.

To be fair, the number of attempts at forcible repatriation has gradually fallen over the years. My general impression is that reports have become fewer. Why this is so, I don’t know. One possible explanation I have is that employers are managing to achieve the same objectives — denying owed salaries, avoiding responsibility for medical treatment, medical leave wages, housing, etc — by doctoring evidence, forging salary vouchers and denying that accidents happened at work, without now having to repatriate workers.

The question is this: Is MOM even aware that this is the lay of the land? Or is MOM, looking at its defect-ridden ‘statistics’, patting itself on its back for ‘only’ 23 cases last year?

Why NGOs play a crucial role

I want to conclude with a philosophical point: healthy, robust NGOs are essential to good governance. When our government tries to cut NGOs out of its processes, it degrades the quality of governance.

This government has a long history of being antagonistic to groups and bodies it does not control,

- borne partly out of a historical fear of emboldening challengers to its dominance,

- partly too out of a defensive instinct to shield itself from critical scrutiny,

- but also driven by a misplaced belief that a more democratic, consultative process involves a price to be paid in efficient decision-making.

However, it never quite realises that efficiency is a very risky thing. It is profoundly injurious to the larger public interest when that vaunted efficiency is applied to implementing bad decisions.

Bad decisions are likelier when the data and information available are defective.

This risk is highest with respect to data and information from and about vulnerable communities, for such communities

- have little meaningful access to those in power (and by meaningful, I mean two-way communication pathways, rather than a top-down pathway),

- are afraid of contact with power, perhaps because they feel trapped by legal provisions, or

- are marginalised and voiceless especially vis-a-vis other social groups (read: employers) with greater access to power and who may wreak retribution on them (the vulnerable) for usurping those other social groups’ pre-emptive access to power.

A wise government is one that is sufficiently self-aware and able to see when its own data collection is impaired by the above conditions; it is one that is thus more careful about making decisions and designing policies on the basis of such data.

Migrant workers constitute a classic vulnerable group. Poverty, unfamiliarity with laws, customs and bureaucratic systems in Singapore, non-fluency in English, lack of family and social networks locally — all these things disadvantage them terribly. On top of such economic, informational and social handicaps, their very right to stay in Singapore is controlled by others (the government and their employers), which in turn curtails their options when it comes to asserting their employment rights. Likewise, their right to change jobs (“as long as permission has been granted,” said Teoh) is contingent on the goodwill of others more powerful than them. Even the simplest thing, such as access to medical care or even a monthly payslip, is controlled by others.

|

In such situations, it may be axiomatic that bureaucrats, who are representatives of coercive power, may never be able to establish honest communication with members of vulnerable communities, and will therefore always be handicapped when it comes to having good data about these communities and their lived experiences. The better thing to do therefore is to rely on intermediaries for contact and information. NGOs are such intermediaries. Not wielding any power in themselves, not connected with social groups whom the vulnerable feel may be oppressing them, NGOs are far better able to earn the trust of vulnerable groups.

The failure to grasp this philosophical point, to see the value in working through NGOs, is a major reason why MOM often finds itself flailing in rough waters. As Teoh’s testimony painfully reveals, there are huge gaps in the ministry’s awareness of the real situation, and frightfully naive beliefs in the fit and effectiveness of its theoretical solutions.

Recommendations will come in part 2

Above, many problems in the employment and welfare of foreign workers have been described. Many policy failures have been highlighted. Are there better solutions? Go to part 2 — coming soon.

Shahin

Shahin

The root of the problem lies in the philosophy and belief system under which this PAP government and its machinery operates. The deficiency in the foreign workers’ (labourers’) protection cannot be less than that which the Singaporean underclass faces. Just imagine the hurdles and bureaucracy the needy has to face to get the merger hand out from ComCare and the numerous help schemes allegedly available. How much sympathy and effort can we expect from a government that is already so lean and mean towards its own citizens? Kevin Teoh is one of many academically capable and university certified pen pushers in the government ministries and statutory boards.

I do hope you have sent this response officially to the committee of inquiry.

Hey, why bother to provide free recommendations? Let the system rot to the core and maybe another riot or two at Chinatown, Geylang, Little India, etc. The PAP government can continue to sleep, but the citizens of Singapore will definitely wake up. And most will know what to do at the ballot box next time. Don’t help the MOM, let it rot. We wait for 2016 to give PAP a tight slap.

Singapore depends on the continuing expansion and growth of slavery for its continuing ability to enrich the already rich and empower the already powerful, not least for its implied message to “mere heartlanders” that if we fail to show sufficiently obsequious obeisance, we could end up like Them. That fear, and the pervasive, pervasively-reinforced racism at the bedrock of Singaporean society, are quite likely the most powerful tools the Lee regime employs to remain in “permanent”, absolute power.

Until that changes, nothing else here will change very much — or at least, not in a very positive way for the vast majority of Singaporeans and other inmates.

Somehow, your article keeps reminding me how we as Singaporeans have been politically neutered by the ruling party, so much so, that calling our nation the Republic of Singapore seemed so wrong. Singapore Pte Ltd seems more in accordance with reality.

Awesome article. Here’s a radical thought. You could put this article on the top of the the Foreign Manpower Management Division’s agenda very easily. Simply email this article and your upcoming recommendations (in full text, not just a link) to Kevin Teoh and CC ALL 84 officers in the 5 departments under him (all available on sgdi, which I’m sure you’re familiar with). That’s guaranteed to get their attention, although this strategy is likely to completely antagonise them and put you on their ultra blacklist. In fact, they’ll likely never talk to TWC2 again. And Kevin Teoh will be hopping mad. But just a really really radical thought that makes me happy.

Like someone said why bother to help the PAP? Let them rot and then the daft 60.1% will finally wake up.

They try to persecute you and others who have been honest with them . Why help these expired talents.

Alex, I do look forward to part 2. However, I also hope that you could discuss this with employers of foreign workers if you have not done so.

A couple of SME employers (of foreign workers) I spoke to are just as distressed when MOM took ‘proactive’ measures.

One was continually asked by MOM to provide accounts relating to salary of his foreign workers. Not issue with that but the demands are like ‘give me two weeks records’ than ‘two months’ than ‘4 months’ and so on. He was peeved and asked if he could give 2 years of records in one shot but earned a rebuke of ‘don’t bargain with me!’

Another was equally distressed by the many many new regulations relating to Workplace Safety and Health Act. What these measures did with all the certifications and courses requirement was that his pool of deployable workers shrinked… but the main contractor or principal are not making allowance for project delays. He ran the risk of deploying ‘uncertified’ but good workers, or face penalty for project delays.

I’m not siding with employers but I think your post can be more objective if the perspectives of employers, good employers can be taken into account.

This MOM Manpower directoris a joke. He should be booted out for not doing his job. He dares to stand up before the committe and say that he is unaware of what problems foreign workers are facing. Is this the quality of civil servants that we have. They sit in air-condition comfort and have no clue or pretend not to know the realities on the ground. So the news papers and the Ngo’s reports are all “fairy tales” in their eyes.

Is the minister also clueless. Do they believe that the committe is just a paper tiger???? Do all these “jokers” think that we are fools.

Full red marks and a BIG F on their report card.